I spent three hours last night contemplating lost youth, so allow me to explain.

On the one hand, I’m no fan of biopics, and I probably won’t watch Bohemian Rhapsody.

Bohemian Rhapsody is a 2018 biographical film about the British rock band Queen. It follows singer Freddie Mercury’s life, leading to Queen’s Live Aid performance at Wembley Stadium in 1985.

I find it interesting and instructive that since the movie was released, there has been so much discussion about Queen’s performance at Live Aid, but unless you’re over forty years of age, it may not be clear to you what Live Aid even was.

The videos pasted here are two parts of a single three-hour BBC documentary, an hour and a half each, and the whole Live Aid story is recapped. It’s solid and filled with information in spite of the many too-cute visual flourishes.

Verily, July 13, 1985 was a bizarre cultural landmark. Flawed, but indisputable. It’s unclear if the millions raised that day accomplished very much in terms of famine relief for Ethiopia, and yet if you were a music fan at the time, Live Aid cannot be forgotten — whether you loved it or hated it.

The following was pulled from my 1985 European travelogue and lightly edited for context. One thing that rings true about the documentary are those memories of walking the streets of London and hearing the concert from every window. I was in Ireland at the time, and the interest level was comparable. It was an amazing thing, indeed.

If nothing else, Live Aid will be remembered as a pioneering use of satellite transmission technology. As many as two million people around the globe tuned in, and while we’re now connected in far more sophisticated and immediate ways, it’s difficult imagining state-of-the-art technology bringing people together in quite the same fashion.

Because: we don’t desire being brought together, do we?

—

At one of the pubs in Sligo, I’d overheard a conversation about a big concert on Saturday, July 13. At first I thought they meant a show in Sligo itself, but then it became clear it was to be televised from Wembley Stadium in London – and finally I made the connection with the magazine I’d previously spotted at the hostel in Paris.

It was Live Aid, Bob Geldof’s epochal day-long, worldwide gig to raise funds for Ethiopian famine relief. I was about to learn the importance of being Irish; Geldof was born and raised near Dublin, and as the guiding force behind the punk-era Boomtown Rats, he doubled as curmudgeonly social critic.

It was a quality Irish conservatives found disconcerting – until the hometown boy made good on a larger stage.

So, never discount the power of national pride. Live Aid was the project of an Irishman, and Ireland was preparing to be quite enamored of this fact, whether or not any of them liked the Boomtown Rats.

On Saturday morning I asked Gerry, who with his wife Mary was my host at their informal bed and breakfast, to direct me to the bus headed for Strandhill. It was a settlement by the ocean at the foot of Knocknarea (nock-na-ray), a 1,000-foot tall limestone hill overlooking the Bay of Sligo. My plan was a morning hike to the top, where a Neolithic burial cairn is located, and then a return to Sligo to watch Live Aid.

As it turned out, Gerry was preparing to drive to the golf course, and so he deposited me at the trail head near Strandhill. It was hazy, muggy and fly-infested, and the path well-traveled. The view from Knocknarea was worth the effort, with majestic vistas of green fields, rocky hedgerows, shimmering sea and the ever-present Benbulbin.

I caught a bus back to Sligo after lunch, showered, and found a seat at a nearby pub. Live Aid was showing on a projection TV. The Irish national television channel had preempted all other programming, and between acts, there were cuts from the live feed to the studio, where an older presenter and Phil Lynott, Thin Lizzy’s singer and bassist, provided what amounted to color commentary.

It struck me that whenever a set ended, and the two television commentators began talking, voices in the pub would be lowered, and the drinkers would pause to listen. This was interesting, though it still was relatively early in the day.

Live Aid was the most ambitious international satellite television production of its time, and Geldof’s creation was subject to rightful criticism: Wasn’t it the very same group of pious pop stars, pumping up their own album sales by means of a charitable “cover,” with little of the money raised ever actually making it to the intended beneficiaries in Ethiopia?

More pointedly for Live Aid’s connection with Africa, why were the acts almost entirely white? Stevie Wonder is said to have refused a slot at the American venue because he had no intention of being the token black.

Ironically, Lynott was a black Irishman, born in London, and he was in the television studio precisely because his band hadn’t been invited to play. How could Bob do that to Phil? They were mates. Still, as Live Aid unfolded, my fellow pub goers were united in praise for the idea – after all, it was Geldof, an Irishman, who’d organized it.

Unfortunately, illness and heroin addiction killed Lynott barely six months later. Did he and Sir Bob ever make up?

At some point later in the afternoon, I walked back to my room to get more money from the secret cash stash. I heard familiar sounds coming from the kitchen, where Mary sat watching U2 begin its star-making Live Aid set.

“It’s U2,” I said. “I love this band. Are you a U2 fan, too?”

“I’ve no idea,” she replied. “But they’re our lads, aren’t they?” We watched together

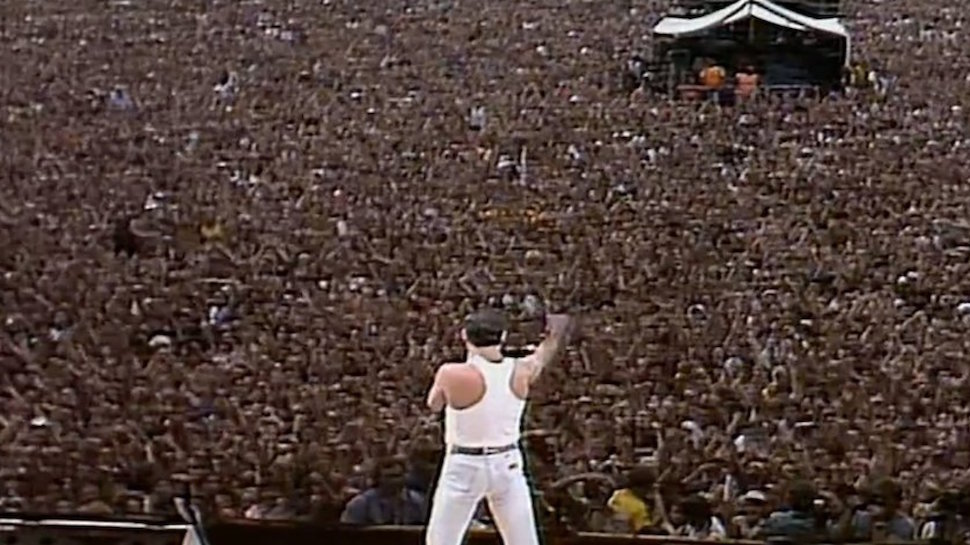

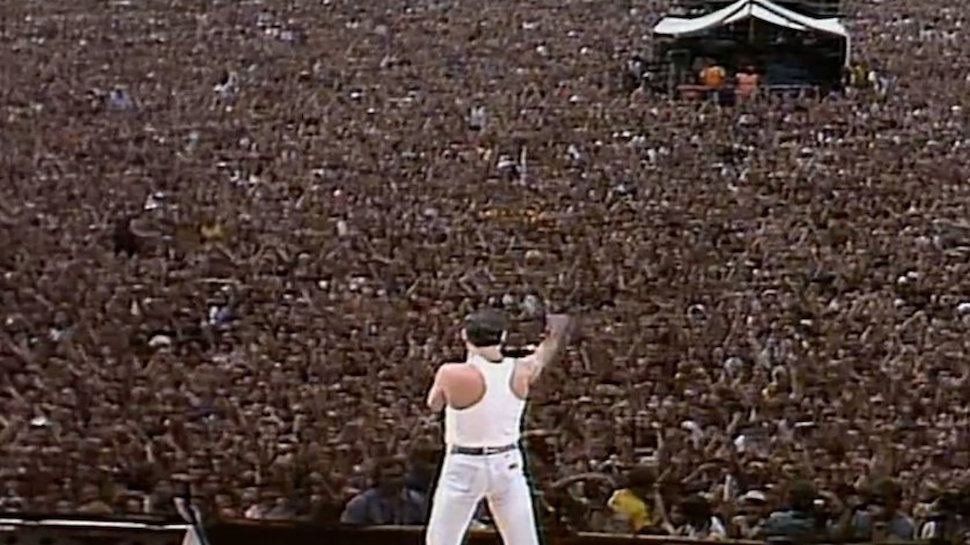

Just as I re-entered the pub, Queen started playing. Like much of the rest of the planet, I was spellbound as Freddie Mercury worked the crowd of 75,000. I’d been only a casual follower of the group, and had not witnessed it on stage.

Queen’s 20-minute set at Live Aid is routinely rated among the most memorable live performances in rock history, and while it may have not been the music I came to Ireland to hear, it’s a personal memory I’ll always cherish.

It gets hazy after that. Back in my room, I listened to the some of the Philadelphia portion of Live Aid on a small radio I’d brought along. I fell asleep, and it would be many years, well into the Internet era, before I ever saw video of what I’d missed.